Creativity and Outside of the Box Thinking in Our DNA

A Childhood Lesson in Innovation

It was a rainy day when the elementary school bus dropped Bob off at the end of National Drive. He had a long walk home, but today he didn’t mind the rain.

Origins of a Visionary Future for Engineering

Inspired by the Moon, Driven by People

Bob was fascinated by the Space Race. Like many young people entering the workforce of his generation, he dreamed of working for NASA, contributing to something larger than life, something that pushed the boundaries of possibility.

Engineering is Meant to Protect Communities

From Blueprints to Safeguards

In 1972, the dam at Buffalo Creek gave way under the weight of continuous rain and years of accumulated mine waste. Over 130 million gallons of black slurry water surged through the hollow in a matter of minutes.

The Spirit of Sacrifice and Service

Leadership Means Showing Up

In the formative years of Orbital, when revenue was unpredictable and payroll loomed large, Bob did something few leaders would consider. He sold his car. It was a quiet, decisive act to ensure that his employees got paid on time. For Bob, leadership was never about image or ego. It was about responsibility.

Flourishing in the Harshest Industrial Environments

Built for Pressure. Trusted in Crisis.

The call came during a crisis. A coal facility had been shut down by regulators, and the site manager—facing serious allegations—needed help fast. Instead of reaching for a legal team, he called Orbital.

Willing to Evolve, Understanding Change is Good

Jump Ropes and Strategy Sessions

By 1979, Orbital faced a critical decision: remain a drafting-focused firm or embrace a broader, more ambitious future. Bob had traveled the country, seen where industry was headed, and knew that drafting alone wouldn’t sustain the company long-term.

Embracing the Reaches of Technology

AutoCAD Before It Was Cool

In 1982, Orbital took a leap that would quietly transform its daily operations. Don Henrich purchased one of the first AutoCAD licenses in Pennsylvania—a decision that didn’t come with fanfare, but would change how the company worked.

Orbital is a Family, and Family Takes Care of One Another

Payroll, Paintbrushes, and a Promise

In the early 1980s, LTV Steel, one of Orbital’s largest clients, declared bankruptcy. Overnight, $1.2 million in receivables disappeared from Orbital’s books. For a company of its size at the time, it was a blow that could have triggered massive layoffs and a long road to recovery.

If You Don’t Ask, The Answer Is Always No

One Elevator Ride = One New Client

In the early days of Orbital, Bob walked into the Amoco Oil building in Chicago—no appointment, no invitation. He stepped up to the receptionist and simply asked to speak with someone in operations.

We Forge Relationships Through Shared Stories

The Steelers. A 747. And Trust.

In the 1990s, Bob wandered over to Three Rivers Stadium and introduced himself to Art Rooney, owner of the Pittsburgh Steelers. What began as a casual, lighthearted encounter grew into a genuine friendship rooted in trust, humor, and shared values.

Hustle

We Answer the Call. Even at Midnight.

By the late 1990s, Bob had built a career on curiosity, intuition, and a relentless drive to understand people. “I’m very observant,” he said. “I watch things. I watch people. I watch how everything works.”

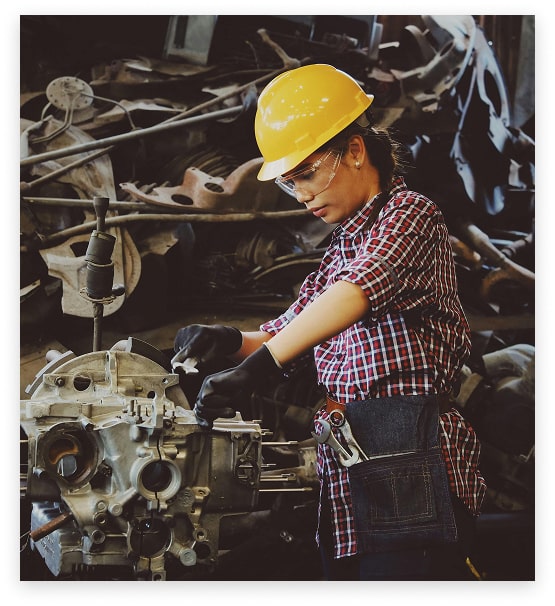

What It Means to Be a Retro-Fit Engineer

Beauty in the Broken

The coal bunker had been there for decades—underused, underappreciated, and running at half capacity. For years, it sat that way, until the client finally decided to bring it fully online. Building new was an option, but not a good one. Permits had taken over a decade. Time and budget were tight. So they called Orbital.

Creativity and Outside of the Box Thinking in Our DNA

A Childhood Lesson in Innovation

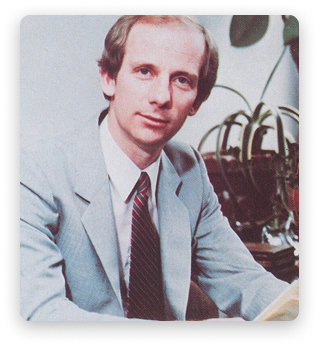

It was a rainy day when the elementary school bus dropped Bob off at the end of National Drive. He had a long walk home, but today he didn’t mind the rain. Bob preferred to endure wet clothes and chilled bones than the wrath from his father, which was imminent after receiving an F on that morning’s spelling test. Despite all the practice, spelling was just hard for Bob. Bob stood for a few minutes in the rain staring at the front door. He felt a sinking feeling in his stomach.

Maybe I could just run away.

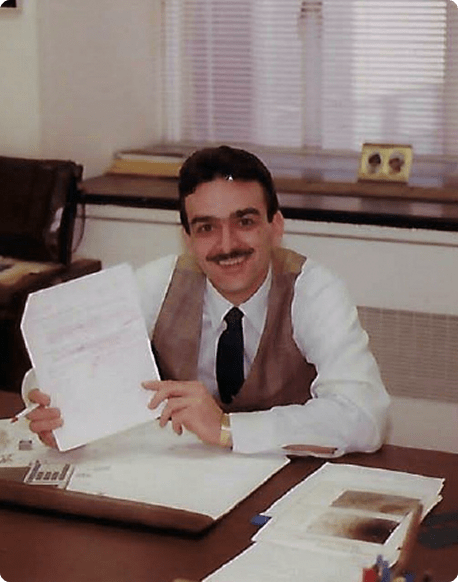

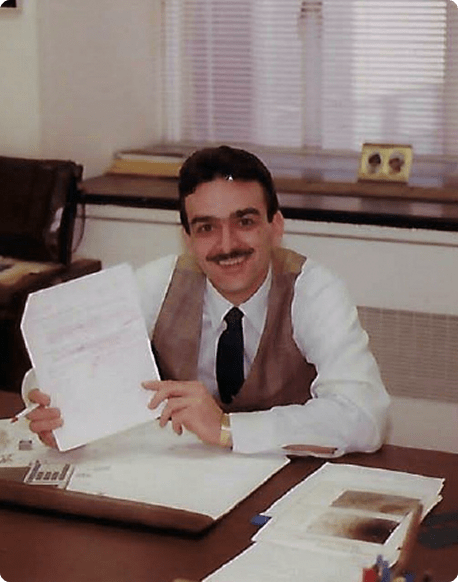

What Bob learned that day he recalls was far more important than how to spell any word. “My father sat me down. He could see I was very upset. So I told him about failing my spelling test. He looked at me and said, ‘It takes a really uncreative person who can only think of one way how to spell a word.’”

Today, Bob looks back on this father-son exchange as a pivotal moment in how he came to see the world. He explained, “This is how my entrepreneurial spirit was born. In an era where everything was so conservative, I was almost given a pass to see things in a different way and solve problems on my own terms. I had no way of understanding at the time how empowering this was, but I certainly do today.”

Origins of a Visionary Future for Engineering

Inspired by the Moon, Driven by People

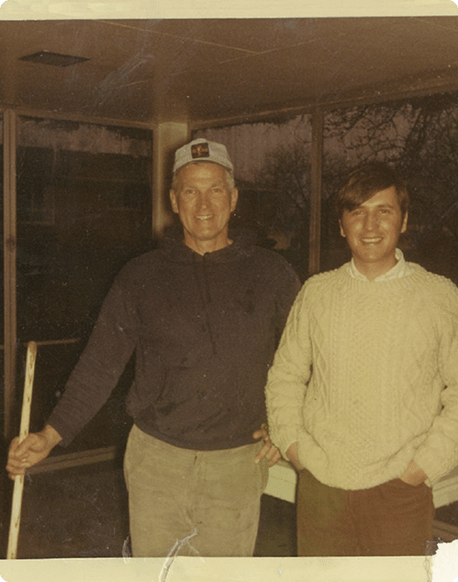

Bob was fascinated by the Space Race. Like many young people entering the workforce of his generation, he dreamed of working for NASA, contributing to something larger than life, something that pushed the boundaries of possibility.

That door didn’t open.

Instead, in 1969, Bob chose to build something of his own. He named it Orbital. The name wasn’t incidental. It reflected his enduring fascination with motion, trajectory, and the forces, seen and unseen, that keep complex systems in balance.

When he saw men walk on the moon, Bob immediately wondered what came next. While the world celebrated a landing, he was already thinking about the future: how we protect our national assets, how technology can continue pushing forward, and how progress depends on people willing to ask the next question.

Engineering is Meant to Protect Communities

From Blueprints to Safeguards

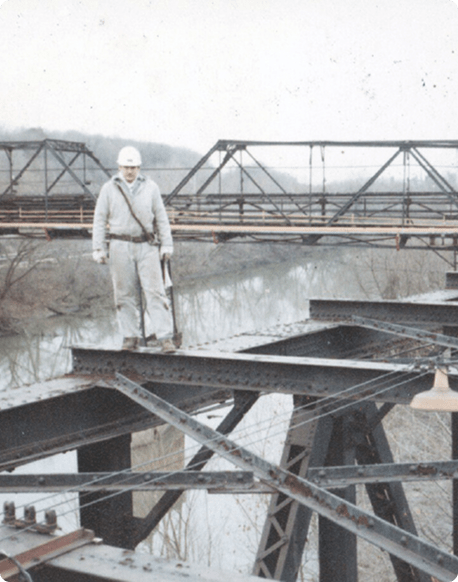

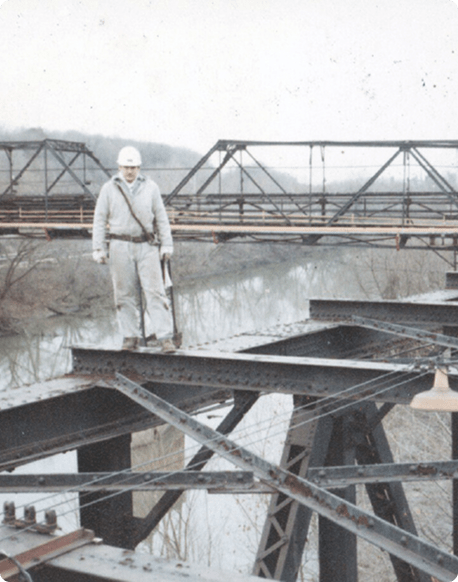

In 1972, the dam at Buffalo Creek gave way under the weight of continuous rain and years of accumulated mine waste. Over 130 million gallons of black slurry water surged through the hollow in a matter of minutes. Towns were swept off their foundations. Families scattered. The flood killed 125 people, injured more than a thousand, and left 4,000 homeless.

Days earlier, Bob had visited Pittston Coal Company’s chairman, Nick Camicia, in New York City, angling for a contract. He didn’t get it then, but they remembered him.

When the dam broke, Pittston called Bob, the brazen kid with a reputation for making sense of an engineering mess.

Bob and Doc Shellhammer drove down to Beckley, West Virginia, where they met the Pittston team at a local bar, The Cat & Fiddle. As the group talked, Doc sat quietly, spooning sugar into a glass of water. He kept adding more—stirring, watching the saturation build—until finally the water couldn’t hold it. He tapped the glass with a knife. The solution spilled across the table.

“That’s what happened to your dam,” Doc said.

Now, they had the Pittston Coal Company’s attention.

What they found in the valley was worse than expected: dams built without engineering principles, structures piled higher as the slurry rose, vulnerable to collapse by design.

Orbital went on to engineer or re-engineer more than 50 similar structures across the region for Pittston Coal Company. They also took on government contracts to inspect and repair 13 high-hazard dams throughout Appalachia.

As the cleanup from the flood made national headlines, it became increasingly clear—not just to Bob, but to everyone—that engineering is work that matters.

The Spirit of Sacrifice and Service

Leadership Means Showing Up

In the formative years of Orbital, when revenue was unpredictable and payroll loomed large, Bob did something few leaders would consider. He sold his car. It was a quiet, decisive act to ensure that his employees got paid on time. For Bob, leadership was never about image or ego. It was about responsibility.

That commitment didn’t come from a boardroom playbook. It came from a deeper place, his service as a U.S. Marine. The discipline, humility, and sense of duty he carried from the Corps became the compass by which he steered Orbital. When the team faced hardship, he leaned in.

Bob believed in the people he hired, in their talent and potential. And he showed it through action. That spirit of service built the foundation on which Orbital would stand for generations.

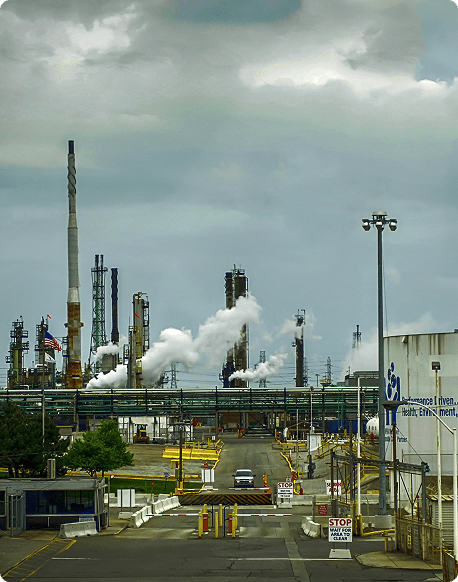

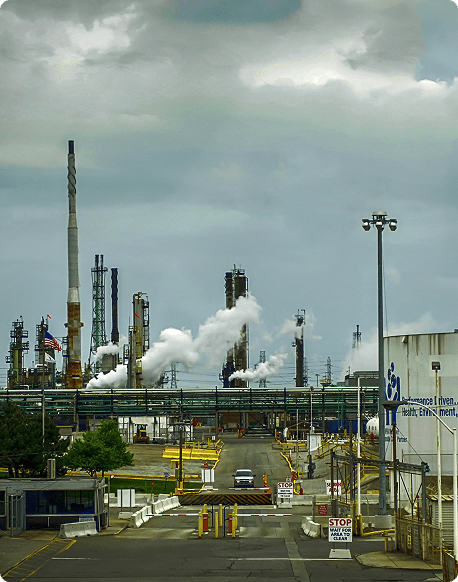

Flourishing in the Harshest Industrial Environments

Built for Pressure. Trusted in Crisis.

The call came during a crisis. A coal facility had been shut down by regulators, and the site manager—facing serious allegations—needed help fast. Instead of reaching for a legal team, he called Orbital.

Doc Shellhammer stepped in.

By that point, Orbital had built a reputation for working closely with regulatory agencies at the federal level. They helped shape what compliance looked like in some of the most complex and hazardous environments in the country.

Doc reviewed the site, studied the plans, and prepared to speak directly to the issues. He laid out the facts clearly: what had happened, why it had happened, and how it could be corrected.

That clarity made an impact. It reinforced what Orbital had come to represent: practical, grounded engineering that worked in the real world, in real time, under real pressure.

The solution was built on trust. Trust between Orbital and its clients. Trust between Orbital and regulators. Trust that when the stakes were high, they would bring more than drawings and calculations, they would bring answers.

Willing to Evolve, Understanding Change is Good

Jump Ropes and Strategy Sessions

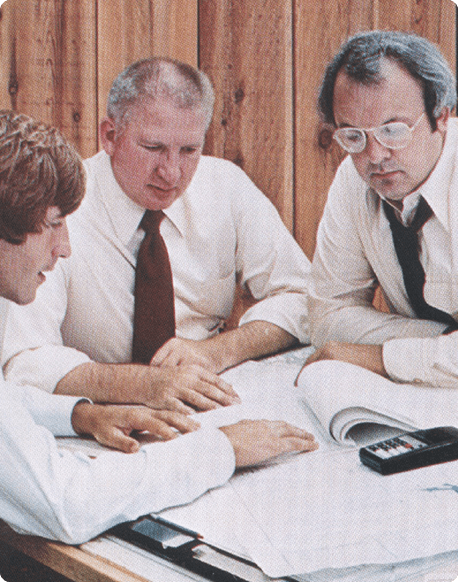

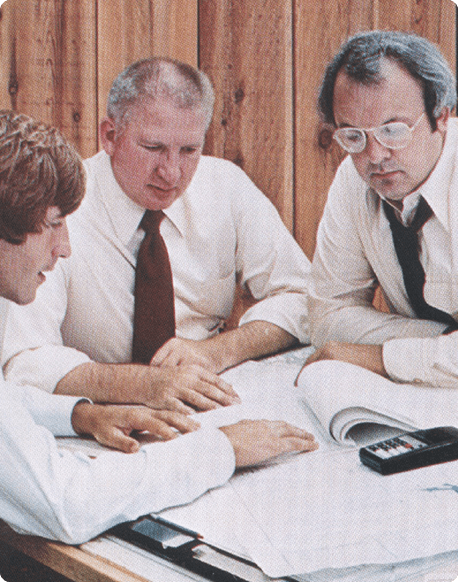

By 1979, Orbital faced a critical decision: remain a drafting-focused firm or embrace a broader, more ambitious future. Bob had traveled the country, seen where industry was headed, and knew that drafting alone wouldn’t sustain the company long-term.

He began working through that decision each evening in Don Henrich’s office.

At 6:00 p.m. sharp, Bob would walk in, remove his tie, and start jumping rope. The rhythm—crack, crack, crack—set the pace for a new kind of strategy session. Don stayed at his desk, reviewing work, while Bob asked questions mid-jump:

“Why did we approach it that way?”

“What else could we have done?”

“Who are we as a company?”

These weren’t hypotheticals. They were tests, measuring not just what Orbital had done, but what it could become.

In those conversations, Bob found clarity. Orbital had engineers who thrived in complexity, who could see paths forward where others stalled. The company’s future was in growing into what it was capable of becoming.

Those rope-and-question sessions marked the turning point. Orbital would evolve. And that evolution would define its second decade of a multi-disciplined engineering firm that focused on programmatic solutions across a multitude of industries that were experiencing similar issues across similar asset classes.

Embracing the Reaches of Technology

AutoCAD Before It Was Cool

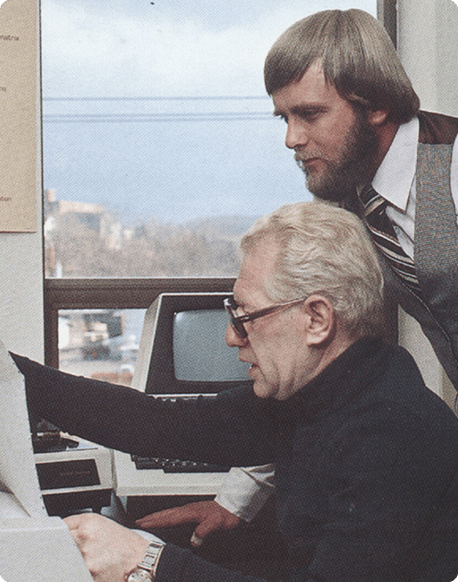

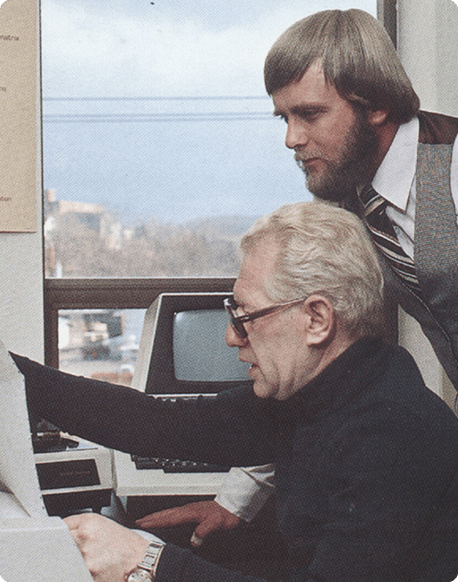

In 1982, Orbital took a leap that would quietly transform its daily operations. Don Henrich purchased one of the first AutoCAD licenses in Pennsylvania—a decision that didn’t come with fanfare, but would change how the company worked.

Until then, everything had been drawn by hand. Drafting tables filled the office, lined with vellum and covered in smudges of graphite and ink. Engineers worked with T-squares, triangles, and meticulous care. It was a craft, and one the team took pride in.

So when the software arrived, not everyone was convinced. It was slow. It crashed. Drawings that once took hours now took days. Some quietly returned to their drawing boards. It wasn’t just a learning curve, it was a cultural shift.

But Don believed in the long game.

He wasn’t trying to chase trends. He saw that technology, when used wisely, could strengthen the integrity of engineering work. Over time, the efficiency grew. Revisions became easier. Precision improved.

The shift to digital tools reflected a deeper belief: that innovation wasn’t about abandoning the past, it was about building on it. And it showed that Orbital would always be a place willing to learn, adapt, and move forward before being forced to.

Orbital is a Family, and Family Takes Care of One Another

Payroll, Paintbrushes, and a Promise

In the early 1980s, LTV Steel, one of Orbital’s largest clients, declared bankruptcy. Overnight, $1.2 million in receivables disappeared from Orbital’s books. For a company of its size at the time, it was a blow that could have triggered massive layoffs and a long road to recovery.

But that’s not what happened.

Bob gathered his leadership team and made a different kind of decision. Instead of letting people go, he handed them paintbrushes.

Engineers were assigned to repaint offices, reorganize the shop floor, tackle backlogged paperwork—whatever kept them contributing, and more importantly, kept them together. Some team members were reassigned to cleaning, others to clerical tasks. Bob made it clear that everyone had value, even if there weren’t billable hours to track at that moment.

“We didn’t have projects, but we still had people. That mattered more,” one employee recalled.

“He wasn’t just saving jobs. He was protecting the spirit of the place.”

There were some layoffs, but they were temporary. Nearly every person affected was rehired within weeks. For those who remained, it wasn’t about keeping busy—it was about staying whole.

Bob never framed it as a grand gesture. But it became part of the company’s DNA. Years later, that time would be remembered as proof of what Orbital truly was: a family.

“You always knew Bob had your back,” another longtime employee said. “When things got rough, he didn’t look for a way out—he looked for a way through, with all of us still in the room.”

If You Don’t Ask, The Answer Is Always No

One Elevator Ride = One New Client

In the early days of Orbital, Bob walked into the Amoco Oil building in Chicago—no appointment, no invitation. He stepped up to the receptionist and simply asked to speak with someone in operations.

As luck would have it, the senior vice president answered his own phone.

Bob introduced himself, made his case plainly, and the conversation turned into a meeting. That meeting turned into a contract. Orbital’s first with Amoco—and one of the most important early chapters in the company’s growth.

Looking back, Bob credited the moment to preparation and courage.

“You have to be prepared to take advantage of luck,” he said.

That story became legend because of Bob’s unwavering belief in initiative, and his understanding that doors don’t always open unless you knock first

We Forge Relationships Through Shared Stories

The Steelers. A 747. And Trust.

In the 1990s, Bob wandered over to Three Rivers Stadium and introduced himself to Art Rooney, owner of the Pittsburgh Steelers. What began as a casual, lighthearted encounter grew into a genuine friendship rooted in trust, humor, and shared values. Art initially saw Bob as quirky, someone fun to be around. But over time, he recognized something more: Bob had a remarkable ability to build lasting relationships in business by simply being himself.

When Art organized an exhibition game in Tokyo to showcase the Steelers and promote Pittsburgh as a hub for international business, he invited Bob to help coordinate the experience and entertain a contingent of business and community leaders. Bob gladly accepted.

“At one point, Bob was up in the cockpit flying the plane,” Art recalled.

“He absolutely does not have a pilot’s license, but he claims he landed the 747 in Tokyo.”

That blend of mischief and charm was part of Bob’s magic. But the relationships Bob formed weren’t just about charisma. They were sustained by substance. Orbital’s client list grew rapidly and enviably, not just because clients liked being around Bob, but because the company consistently delivered quality work.

Even as business became more digital and distant, Bob stayed rooted in personal connection. He visited clients in person, offered honest feedback without fluff, and remained someone people could trust, especially when things weren’t going well. His compassion, candor, and reliability stood out in an industry that often prizes polish over presence.

Clients came to expect the unexpected from Bob, whether he was charming his way into a cockpit or stepping in during a crisis. And that, in part, is why they stayed.

Hustle

We Answer the Call. Even at Midnight.

By the late 1990s, Bob had built a career on curiosity, intuition, and a relentless drive to understand people.

“I’m very observant,” he said. “I watch things. I watch people. I watch how everything works.”

He believed travel was the best education. Whether in Bhutan, Jamaica, or Brazil, Bob didn’t just visit, he connected. He asked questions, studied interactions, and noticed what others overlooked.

When an Alcoa plant in Jamaica teetered on the edge of a strike, Bob flew in. With over 1,000 workers at odds with management and productivity cut in half, he walked the site and listened. One detail stood out: employees’ cars were overheating in the sun. Bob suggested clearing out a warehouse for shaded parking, a small fix that signaled respect. He brought people together, led a morale-building session that turned into a revival, and within a year, the plant was fully operational.

Similar stories followed in South America, where Bob proposed building local health clinics instead of flying injured workers abroad. He called it Catalytic Change Management, the belief that lasting transformation starts with practical, human-centered solutions.

“You always have to get something done,” he said, “or you never get anything done.”

These projects marked a turning point. Bob broadened the company’s scope beyond technical services, into people-centered consulting and change management. That diversification proved to be more than an expansion, it became a shield.

Dick Hipple, who had by this time risen to become CEO of LTV Steel, says this work Bob did to diversify is the reason Orbital could withstand business cycles, the reason Orbital is still a company today. “They hustled,” Dick says. “What Bob did was bring the culture of hustle to the engineering business.”

What It Means to Be a Retro-Fit Engineer

Beauty in the Broken

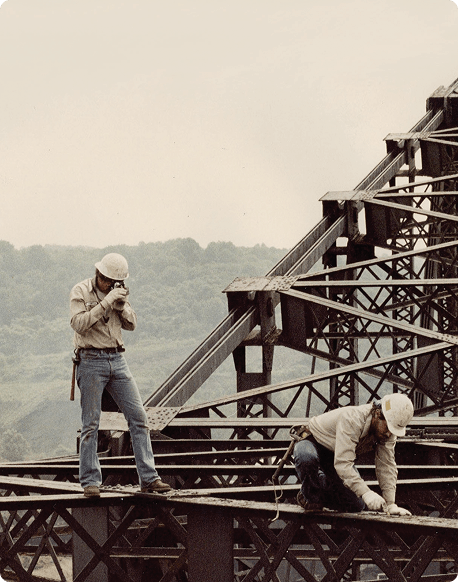

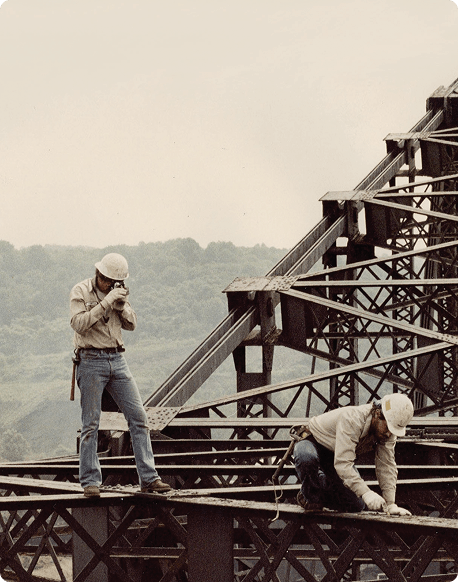

The coal bunker had been there for decades—underused, underappreciated, and running at half capacity. For years, it sat that way, until the client finally decided to bring it fully online. Building new was an option, but not a good one. Permits had taken over a decade. Time and budget were tight. So they called Orbital.

Doc Shellhammer got the call.

He’d worked on the original bunker design years earlier. When he heard the client wanted to revisit it, his first reaction was half a groan. “Are we really doing this exercise again?” he thought. He wasn’t the same agile man who once crawled through tight spaces. But he also knew—deeply—that his calculations from decades earlier still held. The solution hadn’t changed. What was right then was still right now.

Other firms weighed in. Feasibility studies were conducted. Options were explored. But in the end, the most fitting path forward was the original design.

Doc dusted off the old plans, made a few refinements, and Orbital got to work. The repair was completed. The coal bunker, an industrial relic by some standards, was now running at full strength, seamlessly feeding two plants.

“It’s still cranking away over there,” Doc said.

Elsewhere, the Hammond office took on a massive infrastructure overhaul for a Midwestern refinery—one of those projects with a hundred moving parts: rehabbed structures, blast zone upgrades, training centers, sewer systems, and more. It could have been chaos, but it wasn’t. The team walked the site, gathered redlines, collaborated across disciplines, and made the upgrades stick.

In another case, a job site revealed a structure unlike anything the team had seen—steel billets instead of beams, making it nearly impossible to slide the necessary equipment into place. Cutting the structure wasn’t an option. It might collapse. So the team did something different.

They redesigned the equipment.

“We worked with our vendor to re-engineer their equipment so it was narrow enough to fit,” Brent said. “We saved our steel client hundreds of thousands of dollars and the potential risk of future damage.”

Just thoughtful problem solving—layered with memory, creativity, and precision. The kind of engineering that requires knowing what you’re looking at and believing it’s still worth something.